Banff, AB, Canada

14 August 2021

Solo

A smoky adventure

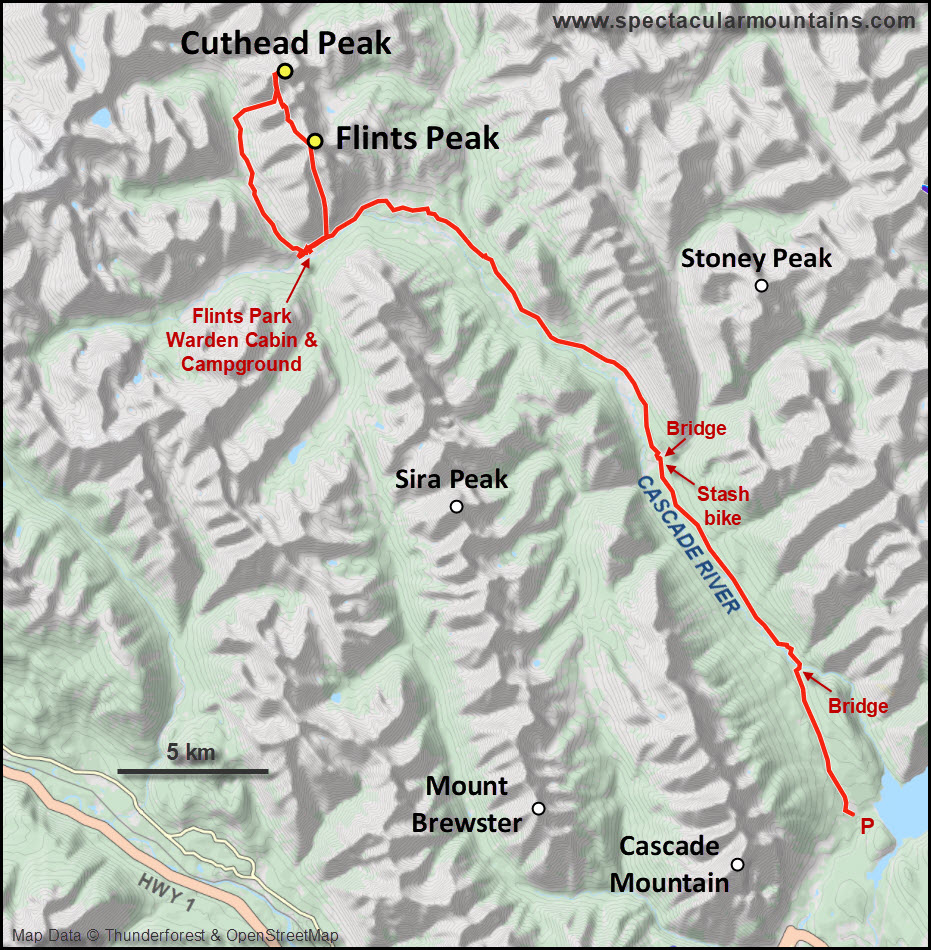

Admittedly, conditions weren’t ideal for my weekend adventure to Banff National Park. It was hot (31 deg), humid, and unusually smoky even by Rockies fire season standards. The weather forecast had called for clear and sunny days, but that was not the case when I pedalled down the Cascade Fire Road at 8 AM in the morning.

Still, I was in great spirits as I had just bought a proper mountain bike with full suspension which turned out to be such a joy compared to the old steel goat I’d been riding for years. What a huge difference this makes, finally my bike approach was enjoyable! Also, I was really looking forward to exploring yet another “unknown” peak (at least to me) and trying to see if there was a route up it. Cuthead Peak sits in a pretty remote corner of the park and getting there would be half the adventure. My aim was to combine it with Flints Peak to the south on the first day, then scramble up Stoney Peak “on my way out” on the second day.

The Cascade Fire Road is perfect for biking but unfortunately you’re only allowed to bike the first 14.8 km to Stoney Creek. Very very few people venture out here, whether it’s on foot or on horseback, and the road is still in excellent shape further north so there is really no reason why bikes shouldn’t be allowed. The old bridge over Stoney Creek was washed out years ago but fortunately Parks Canada has built a new foot bridge so crossing the sometimes raging waters isn’t an issue anymore.

After stashing my bike in the bush I set off on the long, long hike towards Flints Park. It felt a bit eerie to be all alone on such a good, wide road in the middle of nowhere and I wondered where “everyone else” is – the outfitters, horse riders, Banff athletes, weekend hikers, and scramblers like me. I guess the smoke was the answer, it was unfortunate but I could hardly see the mountains around me. One thing that made me curious were the number of unmarked trails branching off to the side, especially after the road turns NW. There is a signed “Cascade River Trail” that’s probably more scenic and easier for horses down in the valley, but presumably less efficient for hikers. Various other trails are begging to be explored and I continue to be puzzled by the fact that no detailed trail maps exist for such a famous national park in Canada!

After about three hours of hiking I reached the backcountry campground at Flints Park, situated right by the North Cascade River and across from the Flints Park warden patrol cabin. I dropped off my heavy overnight pack, had lunch, and switched to my much lighter day pack with just the essentials (a headlamp, SOS device, spare batteries, extra food, toque and gloves are always in my bag).

Flints Park is an interesting place, both geographically and historically. The Cascade River valley broadens at the intersection of several tributaries coming off the side valleys, ending in a flat expanse of meadows, bogs and forest and overlooked by the dramatic cliffs of Flints Peak’s southern outliers. Four key trails come together here: Forty Mile Creek Trail from the south, Badger Pass Trail from the west, North Fork Trail from the north, and Flints Park Trail from the east (which I had come in from). The historic patrol cabin must’ve been in existence for several decades and there is also a large outfitter’s camp nearby – “Flints Camp” – that was established in 1971.

I checked out the well-maintained patrol cabin after lunch but no one was home and the windows shuttered and doors locked with nail boards in front of them to prevent uninvited bears to enter. And uninvited “tourists” like me! Of course, patrol cabins are off-limits to visitors anyway. Other than the small main cabin, there was a small stable and an enclosure for the horses, a small shed for chopped wood and tools, a nearby outhouse, and a solar-panel contraption for power. Nestled in the trees, the cabin looks out to the broad river valley and has some picnic tables in an open grassy area between the building. Quite idyllic actually.

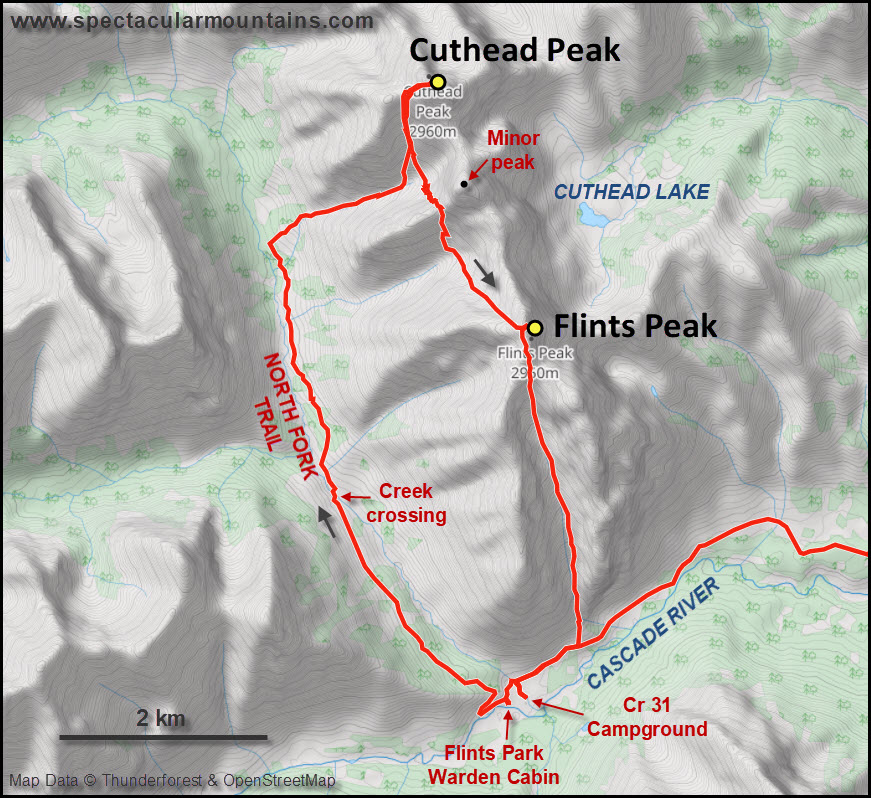

It was already 2 PM, so high time to get moving since I still had two peaks to climb. North Fork Trail is in pretty good shape but you can tell it rarely sees traffic. The trail first stays on the west side of the creek, then switches to the other side and continues north from there. Thankfully, there was lots of water flowing in the creek (I wasn’t able to rock-hop it), which was my last source of water for basically the rest of the day.

After following the North Fork Trail for about 5.5 km a conspicuous drainage appeared on my right. The drainage was hot and dry, with tons of rubble, so not the most pleasant place to hike up. Nonetheless, it did take me directly to a small and barren valley on the southwest side of Cuthead Peak from where I could see the summit. I trudged up a broad slope of brown shale to the west ridge, then scrambled much steeper terrain on grey limestone towards the summit. The west ridge is pretty wide at first and the cliffs that appear near the top can be bypassed on climber’s right with some moderate scrambling on slabs and rock ribs. Soon after I was back on the now narrow ridge crest and the highest point. There was no summit cairn yet, so this might even be an FRA (first recorded ascent), who knows.

Unfortunately, the smoke situation hadn’t improved and it actually seemed worse up here than down in the valley. Everything was shrouded in an orange-white haze, including Cuthead Lake to the east which I had really wanted to see. But that’s how it goes sometimes, you can’t always have it all.

It was now 6 PM and I still had Flints Peak to climb! My plan was to retrace my steps to the barren valley, then use easy scree slopes to hike up and over the western extension of a smaller intervening peak, and eventually up to the west side of Flints Peak. This scree band is formed by the same shale layer I used to trudge up to the west ridge of Cuthead Peak. Although this route was a bit tedious and involved about 500 m of additional gain and loss, it was still better than going all the way back down to North Fork Trail and then tramping up again in the drainage further south. Following the ridge top to connect Cuthead with Flints directly didn’t look like a feasible option from below – several large vertical cliffs would’ve made this a time-consuming technical climb.

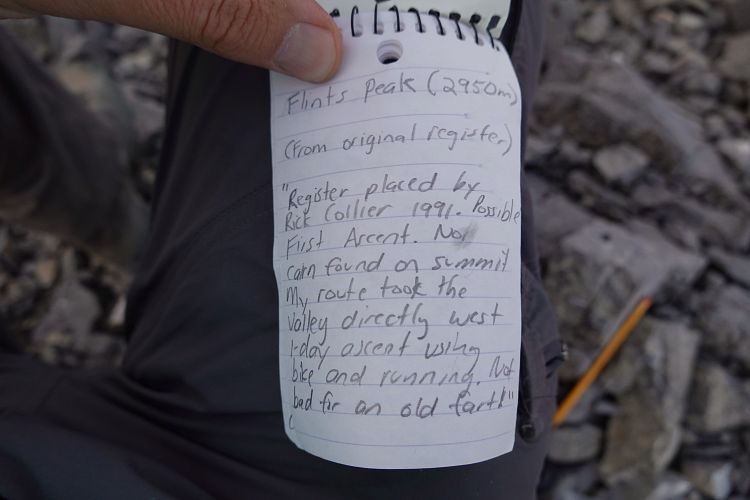

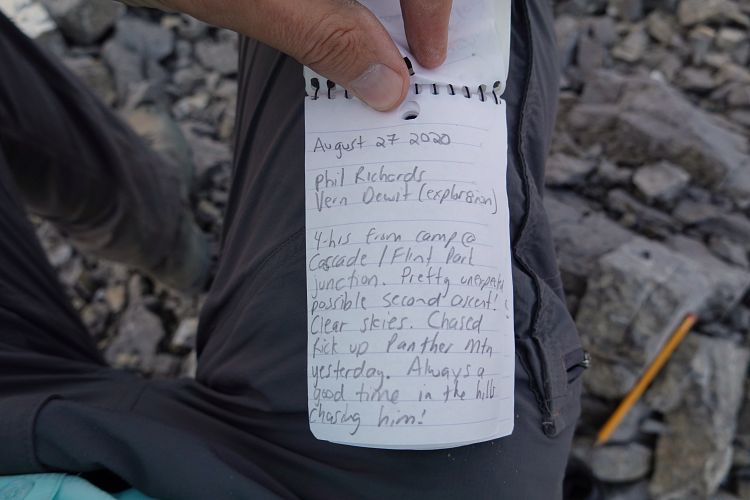

My route worked out as planned and about 2.5 hours after leaving Cuthead Peak I got to the summit of Flints Peak. There is a short, slightly steeper section just below the summit but overall it was much easier than the west ridge of Cuthead. As I expected, Rick Collier’s original summit register from 1991 still only had two other names in it – Vern Dewit and Phil Richards, who had visited a year earlier. They had come up via the broad valley directly south of the summit, which was to be my descent route.

This descent turned out to be straightforward and quick. I found it absolutely astounding that I could still see some of their boot tracks in the soft scree below the summit where you contour around a steep and exposed part of the north-south summit ridge on the west side. The broad valley to the south is filled with heaps of talus which can be hard on the knees, but there was almost no routefinding needed and the terrain was easy, which was gladly welcomed by my tired brain. The valley narrows lower down and leads directly back to the trail by the Cascade River. Just above treeline the otherwise dry valley drainage suddenly revealed a gushing flow of cold, refreshing water which I eagerly jumped on after hours of hiking in a dry, smoky, and barren landscape.

I was back at camp just before it got too dark to hike without a headlamp. There were still no other people around and it definitely felt a bit lonely when I concluded my day eating my dinner at the picnic table in the dark. Though exhausted and a little disappointed by the smokey views, I felt happy I had made it this far and everything had worked out without a hitch.

|

Elevation: |

3027 m (Cuthead Peak) |

|

2974 m (Flints Peak) |

|

|

Elevation gain: |

2800 m (elevation loss: 2420 m) |

|

Time: |

14.0 h |

|

Distance: |

48.1 km (of which 15 km by bicycle) |

|

Difficulty level: |

Moderate (Kane), T4 (SAC) for Cuthead Peak |

|

Easy for Flints Peak |

|

|

Comments: |

Stats refer to bike & hike to Flints Park backcountry campsite, ascent of Cuthead and Flints, and return to the campsite. |

|

Reference: |

Own routefinding |

|

Personal rating: |

4 (out of 5) |

NOTE: This GPX track is for personal use only. Commercial use/re-use or publication of this track on printed or digital media including but not limited to platforms, apps and websites such as AllTrails, Gaia, and OSM, requires written permission.

DISCLAIMER: Use at your own risk for general guidance only! Do not follow this GPX track blindly but use your own judgement in assessing terrain and choosing the safest route. Please read the full disclaimer here.